Yellow-eyed penguin, Megadyptes antipodes (Hombron and Jacquinot 1981)

"big southern diver"

The Maori name is hoiho, noise maker

Unless otherwise stated, the information contained on this page is taken from:

Seddon, P. J., Ellenberg, U. and van Heezik, Y. 2013. Yellow-eyed penguin (Megadyptes antipodes). Pp 91-110 In Penguins, natural history and conservation. Eds. P. G. Borboroglu and P. D. Boersma. University of Washington Press, Seattle & London.

Photos by Hiltrun Ratz unless otherwise stated.

Description of the species:

|

Adult:

The Yellow-eyed penguin is about 65cm average standing height tall and weighs between 4.2 and 8.5kg. It has a distinctive pale yellow, uncrested band of feathers passing across the nape and around the eyes. The forecrown, chin and cheeks are black-flecked yellow. The sides of the head and the fore-neck are light fawn-brown; and the back and tail are slate blue (paler and browner near the moult). The chest belly, front thighs, and the leading edge and underside of the flippers are white. The bill is long and relatively slender and red-brown-pale cream the eyes are yellow; the feet are pale to deeper pink dorsally and black-brown ventrally. Juvenile: They lack the pale yellow- band and have a paler eye and paler dorsal head. Sexes look alike, with males being larger than females. A combination of head and foot measurements sex 93% of the adults correctly; using morphometrics to sex fledglings is less reliable. The head is measured from the tip of the beak to the back of the head. Males average 143.5mm ± 2mm, females average 137.1mm ± 3mm. |

Taxonomic status:

Recent research has overturned some long-held beliefs about the mono-generic status of Yellow-eyed penguins. A combined analysis of ancient and modern DNA and ancient and modern penguin bone structure revealed the presence on the New Zealand South Island of a a sister species Megadyptes waitaha. Up until about 1500 AD Yellow-eyed penguins were restricted to Auckland and Campbell Island groups, while the mainland was occupied by M. waitaha. It is thought to that M. waitaha was harvested to extinction and that its disappearance opened the way for straggler Yellow-eyed penguins from the sub-antarctic to gain a foothold on the mainland, where a change in harvest patterns by humans and a loss of large marine mammals allowed them to rapidly expand into the population we see today. The endemic Yellow-eyed penguin is now the only extant member of the genus Megadyptes remaining in and restricted to the New Zealand region.

Range and distribution:

Distribution of Yellow-eyed penguins

Distribution of Yellow-eyed penguins

Yellow-eyed penguins breed on the southeast coast of New Zealand's South Island (mainland), on Stewart Island and adjacent islands, and in the sub-antarctic on Auckland and Campbell Islands.

On the New Zealand mainland they breed in four distinct breeding regions: the Catlins, Otago Peninsula, North Otago and Banks Peninsula.

On Stewart Island they breed along the northeastern and eastern shores, as well as on a range of island outliers, most importantly Codfish Island, around the exit of Paterson Inlet including Bench Island and further south in Port Pegasus.

Management of this species has proceeded as if it exists as one large management unit, stretching from Banks Peninsula to Campbell Island. Band recoveries indicated very little or no movement between the sub-Antarctic and mainland populations, or from north to south. Early genetic studies showed genetic separation between the South Island and Auckland and Campbell Islands.

More recent analysis revealed two genetically and geographically distinct populations: the South Island (including Stewart Island) and the sub-Antarctic confirming that there is no signifiant migration of Yellow-eyed penguins between the sub-Antarctic and mainland New Zealand and that these populations should be managed as separate units.

On the New Zealand mainland they breed in four distinct breeding regions: the Catlins, Otago Peninsula, North Otago and Banks Peninsula.

On Stewart Island they breed along the northeastern and eastern shores, as well as on a range of island outliers, most importantly Codfish Island, around the exit of Paterson Inlet including Bench Island and further south in Port Pegasus.

Management of this species has proceeded as if it exists as one large management unit, stretching from Banks Peninsula to Campbell Island. Band recoveries indicated very little or no movement between the sub-Antarctic and mainland populations, or from north to south. Early genetic studies showed genetic separation between the South Island and Auckland and Campbell Islands.

More recent analysis revealed two genetically and geographically distinct populations: the South Island (including Stewart Island) and the sub-Antarctic confirming that there is no signifiant migration of Yellow-eyed penguins between the sub-Antarctic and mainland New Zealand and that these populations should be managed as separate units.

IUCN status: Endangered

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species: downloaded 9 June 2015

This species is listed as Endangered because it is confined to a very small range when breeding, in which its forest/scrub habitat has declined in quality. Its population has undergone extreme fluctuations and is now thought to be in overall decline (year published: 2012 and assessed by BirdLife International).

Natural History:

The present-day distribution of Yellow-eyed penguin breeding sites corresponds to the pre-European distribution of cool coastal hardwood forest. Currently, breeding occurs in mature coastal forest, regenerating coastal scrub, but also in pasture, windbreaks of planted exotic trees, and relatively exposed cliffs. Access to breeding and loafing sites may be via sandy or pebble/rocky breaches, or rocky platforms. The majority of nests are sufficiently spaced among dense vegetation to be visually isolated.

Yellow-eyed penguins select well-concealed nest sites under dense vegetation with both sexes contribution to nest building. The nest itself is an open shallow bowl made of twigs, grass, and leaves. Most birds return to the same general nest area each year. Several nest sites can be occupied before laying and nest sites can be different from year to year or be retained for up to seven successive seasons. Nearly three-quarters of breeding pairs remain together for more than one season, with divorce the cause of about 13% of pair bond changes.

Yellow-eyed penguins select well-concealed nest sites under dense vegetation with both sexes contribution to nest building. The nest itself is an open shallow bowl made of twigs, grass, and leaves. Most birds return to the same general nest area each year. Several nest sites can be occupied before laying and nest sites can be different from year to year or be retained for up to seven successive seasons. Nearly three-quarters of breeding pairs remain together for more than one season, with divorce the cause of about 13% of pair bond changes.

Breeding:

|

Little is know about pair formation which may take place at any time during the annual cycle. Pairs may be seen together at potential nest sites as early as July-August. The pre-egg phase is characterised by intermittent nest occupation, usually by lone males and pairs during the day and pairs overnight. Females tend to remain at the nest throughout the laying period but may leave for a single day between eggs. Males accompany the female at the nest overnight and stay with the single egg during the females absence during the day.

The mean laying date is 24 September on the Otago Peninsula but can occur later at more southern locations, such as Nugget Point, and for Campbel Island it can be up to two weeks later than the mainland. A clutch of two eggs is usually laid 3-5 days apart. Young birds are more likely to lay a single egg. Some individual females lay consistently early or late, regardless of their age, and egg size generally increased with the age of the female. No replacement clutches are laid. Incubation starts after the laying of the second eggs. Both sexes incubate the eggs for about 2 days and then change places. |

|

Hatching is almost synchronous and eggs hatch within one day of each other. Hatching success over 6 seasons on the Otago Peninsula ranged between 81% and 87%.

Rearing chicks can be divided into two phases: the guard phase when the chick is constantly attended for between 40 and 50 days at the nest, and the post-guard phase when chicks are left alone at the nest during the day and fed in the late afternoon or early evening when the adults come ashore, usually within 1-3 hours of each other. By day 20 the sparse primary down has been replaced by thicker secondary down, and after 25 days chicks no longer require brooding and may wander from the nest site, often congregating with chicks from adjacent nest sites to form small groups of 4-6 and up to 12 chicks, particularly in more open habitat and when nests are close together. Hatching weight is about and mean fledging weights from the Otago coast ranged between 4.1kg and 6.2kg. Variation in food availability can result in considerable inter-annual variation in fledging weights and chick mortality. |

6 week old chick

6 week old chick

Accident, predation and starvation are the major causes of chick death and disease may also be a concern. Early deaths are usually accidental, such as when small chicks are crushed, or can be due to the failure of the parents to feed the chicks. Chicks are most likely to be killed by predators between 5 and 20 days after hatching but remain vulnerable until 40-50 days after hatching. Starvation is uncommon but may occur after 9 weeks. When food availability was sufficiently poor to result in starvation of chicks both chicks lost weight at similar rates and no brood reduction mechanisms were evident. Fledging of chicks occurs after about 106 days. Little is known about the movements of newly fledged juveniles other than that in most years they move north and may spend most of the winter at sea, although in good foo years, they will remain in the vicinity of their natural area and can be seen onshore from time to time.

Additional note from Penguin Rescue: The chicks are about adult size aged 8 weeks and are still covered in down feathers. They are slowly replaced starting with the insides of the flippers and tail feathers. The belly is finished and white before the back has turned blue and last is the neck and head. The chicks are usually down-free by three months but stay for another 2 weeks being fed by the parents. They will require about 1kg of fish a day. For more information about breeding success at the colonies cared for by Penguin Rescue, please go to the Advocacy and reports page for our annual reports.

Prey

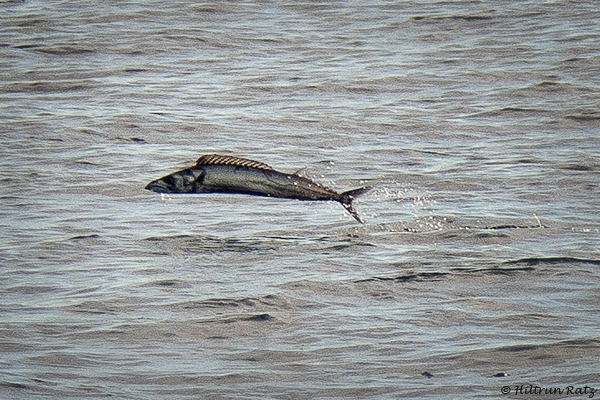

Underwater swimming Yellow-eyed penguin

Underwater swimming Yellow-eyed penguin

Yellow-eyed penguins ate 26 prey species across seven mainland localities between 1984 and 1986 with fish comprising 87% of the weight and 91% of the total number of prey items and arrow squid Nototodarus spp. making up the remainder. Sprat Sprattus antipodum was most frequently taken but also red cod Pseudophycis bachus, opalfish Hemerocoetes spp., ahuru Auchenoceros punctatus, silversides Argentina elongata and blue cod Parapercis colias.

Most prey are <200mm in length. considerable variation in species composition and meal sizes occurs between years and different localities. Prey species are both pelagic (mid-water) and demersal (bottom-dwelling) in habit. Juvenile penguins ate more squid and less fish than did adults.

Most prey are <200mm in length. considerable variation in species composition and meal sizes occurs between years and different localities. Prey species are both pelagic (mid-water) and demersal (bottom-dwelling) in habit. Juvenile penguins ate more squid and less fish than did adults.

Foraging

Three adult Yellow-eyed penguins out fishing

Three adult Yellow-eyed penguins out fishing

Most Yellow-eyed penguins forage in the mid-shelf region between 2 and 25km offshore, diving to depths of up to 40-120m to obtain bottom-dwelling fish species. Breeding Yellow-eyed penguins make two kinds of foraging trips: day trips that ranged between 12 and 20km from the coast and shorter evening trips of less than 7km. Diving behaviour is mainly benthic. While foraging trips are very consistent, considerable inter-individual variation exists in how far offshore birds feed: most are mid-shelf foragers while others are active >16km from the coast. Failed breeders and nonbreeders travelled farther and longer than breeding birds.

Predators

|

One of the most significant impacts on Yellow-eyed penguin productivity is predation of chicks (particularly chicks between 5 and 20 days of age) by a suite of introduced mammalian predators, including feral cats (Felis catus), ferrets (Mustela furo) and stoats (Mustela erminea). Annual chick mortality ranges as hight as 63% in the absence of effective predator control. Rats (Rattus norvegicus) may prey on small chicks: there are two known instances of chicks wounded by rats on Campbell Island. On the the main Auckland Islands, pigs (Sus scrofa) probably kill both chicks and adults. Otherwise adult penguins appear not to be at great risk from exotic terrestrial predators, except for dogs. Mustelids may also take eggs.

Sharks, barracouta (Thyrsites atun), fur seals (Arctocephalus forsteri) and New Zealand sea lions (Phocarctos hookeri) take or injure Yellow-eyed penguins at sea. The population-level significance of these causes of mortality is not known. As fur seal and New Zealand sea lion numbers are increasing around the New Zealand mainland coastline, at-sea predation of penguins likely will increase. An individual sea lions can take Yellow-eyed penguins at rates that could extirpate small local populations, but this habit is not widespread in the sea lions population. Predation of Yellow-eyed penguins by sea lions has been observed by at Campbell Island in 1988, but predation levels were considered to be low and due to some individuals adopting this predatory behaviour.

|

Moult

|

Moult takes place between late February and late March, on average 22 days after chicks fledge, but more recently has extended into April. Birds remain on shore for about 24 days. Juveniles and failed and nonbreeders commence moulting before successful breeders. Though most breeding birds moult on or near their nest sites, many move north, some as far as away as Canterbury, Kaikoura, Cape Campbell, and, rarely, the lower North Island.

|

|

Main threats

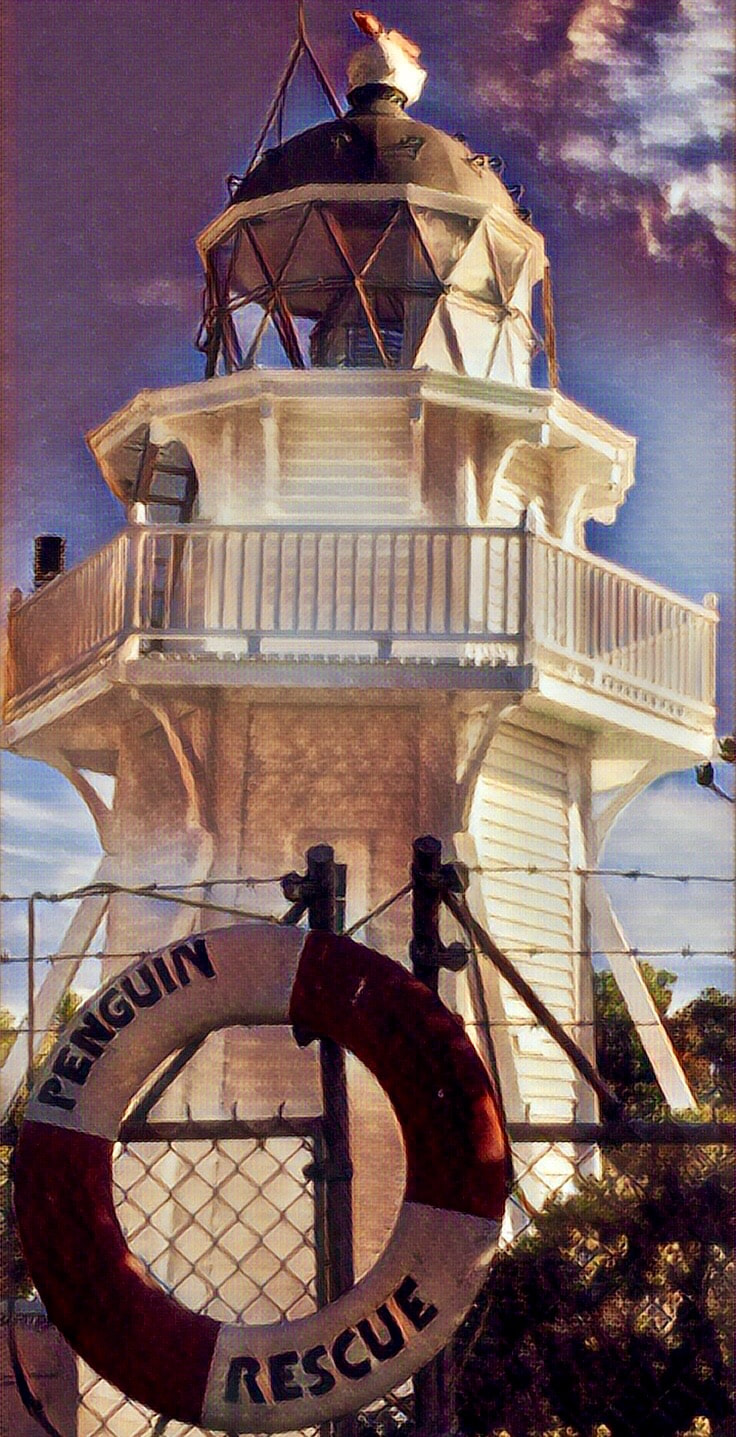

At the colonies cared for by Penguin Rescue, nest boxes have been used to create instant nesting opportunity for the penguins. These are still popular despite the mature forest now also available.

At the colonies cared for by Penguin Rescue, nest boxes have been used to create instant nesting opportunity for the penguins. These are still popular despite the mature forest now also available.

Terrestrial threats:

On land, habitat degradation has the greatest impact on the species. Breeding habitat changes and loss and fragmentation of habitat reduces reproductive success through predation, disease, human disturbance, heat stress and hypothermia if chicks get wet.

Loss of mature coast forest may be responsible for historic declines in Yellow-eyed penguin populations and may force penguins to nest in possibly sub-optimal habitats, where they may face greater heat stress on land during breeding. However, there is evidence that penguins are able to breed and fledge chicks in even very modified pasture habitats. The effects of predation were thought to be ameliorated (but not eliminated) through the creation of areas of rank vegetation that could support fewer rabbits (primary prey of cats, ferrets, and stoats) and hinder access o these predators into and through penguin breeding sites. Quantification of predator movement and the relative abundance of predators and prey do not support this "vegetation buffer" hypotheses. The evidence suggests buffer zones may attract predators, possibly through increased abundance of the prey species such as mice and small bids. Inadequately controlled dogs continue to cause problems on penguin landing beaches.

On land, habitat degradation has the greatest impact on the species. Breeding habitat changes and loss and fragmentation of habitat reduces reproductive success through predation, disease, human disturbance, heat stress and hypothermia if chicks get wet.

Loss of mature coast forest may be responsible for historic declines in Yellow-eyed penguin populations and may force penguins to nest in possibly sub-optimal habitats, where they may face greater heat stress on land during breeding. However, there is evidence that penguins are able to breed and fledge chicks in even very modified pasture habitats. The effects of predation were thought to be ameliorated (but not eliminated) through the creation of areas of rank vegetation that could support fewer rabbits (primary prey of cats, ferrets, and stoats) and hinder access o these predators into and through penguin breeding sites. Quantification of predator movement and the relative abundance of predators and prey do not support this "vegetation buffer" hypotheses. The evidence suggests buffer zones may attract predators, possibly through increased abundance of the prey species such as mice and small bids. Inadequately controlled dogs continue to cause problems on penguin landing beaches.

|

Disease:

Yellow-eyed penguin adults and chicks appear periodically to succumb to outbreaks of disease. The major die-off of adults (estimated at 31% of the mainland population) in 1990, in which a number of agents were suggested, including avian malaria, was not confirmed to be caused by a specific agent. in the 2002/03, 2004/05, 2006/07 and 2008/09 breeding seasons, young chicks inn mainland breeding sites because infected with a disease later described as diphtheritic stomatitis, caused by a Corynebacterium (Corynebacterium amycolatum). This bacterium is naturally present in healthy penguins. Despite repeated disease outbreaks, the trigger that causes diphtheritic stomatitis in some years and in some areas is still little understood even though the outbreaks thus far have been recorded biennially. Any stressor that weakens the immune system, ranging from starvation to an unknown virus, could potentially be responsible. Although some chicks responded to antibiotic treatment, mortality in some breeding areas was as high as 86%; renal failure due to dehydration was suggested as the primary cause of death. Corynebacterium also affected chicks on Stewart Island, where it may have subsequently contributed to chick mortality due to Leucocytozoon in 2006-08. There has been some recent evidence of disease-related mortality of adults since 1990, and some evidence of disease affecting adults and chicks on the sub-Antarctic islands. |

|

Human disturbance is a huge issue at Katiki Point. Here a group of tourists tower over an adult that has just returned from fishing and is trying to feed its chicks.

The 40 000- 50 000 uncontrolled visitors to Katiki Point caused over 50% mortality of chicks less than 2 weeks old in the 2014/15 season. For more information see our human disturbance page and annual report.

Human disturbance is a huge issue at Katiki Point. Here a group of tourists tower over an adult that has just returned from fishing and is trying to feed its chicks.

The 40 000- 50 000 uncontrolled visitors to Katiki Point caused over 50% mortality of chicks less than 2 weeks old in the 2014/15 season. For more information see our human disturbance page and annual report.

Human disturbance

This species is vulnerable to disturbance by humans, including tourists, researchers and managers. Available evidence suggests that carefully regulated tourist viewing of penguins does not carry measurable impact. However, unregulated and relatively high intensity disturbance by tourists is associated with reduced breeding success and lower chick weights at fledging, which results in lower first-year survival and recruitment probabilities. Contrary to what could be expected, birds that continued to breed despite frequent disturbance do not habituate to human proximity but appear to be sensitized and show stronger heart rate and hormonal stress responses to human disturbance. Hence, penguins exposed to unregulated tourism are not only disturbed more often, each disturbance event is more costly for the affected birds and disturbance effects accumulate, potentially leading to poorer breeding performance.

This species is vulnerable to disturbance by humans, including tourists, researchers and managers. Available evidence suggests that carefully regulated tourist viewing of penguins does not carry measurable impact. However, unregulated and relatively high intensity disturbance by tourists is associated with reduced breeding success and lower chick weights at fledging, which results in lower first-year survival and recruitment probabilities. Contrary to what could be expected, birds that continued to breed despite frequent disturbance do not habituate to human proximity but appear to be sensitized and show stronger heart rate and hormonal stress responses to human disturbance. Hence, penguins exposed to unregulated tourism are not only disturbed more often, each disturbance event is more costly for the affected birds and disturbance effects accumulate, potentially leading to poorer breeding performance.

All Yellow-eyed penguins at Penguin Rescue colonies have been fitted with sub-cutaneous transponders or chips. This is an old photo of a penguin with a flipper band that has sprung open.

All Yellow-eyed penguins at Penguin Rescue colonies have been fitted with sub-cutaneous transponders or chips. This is an old photo of a penguin with a flipper band that has sprung open.

Human disturbance of Yellow-eyed penguins in the form of well-intentioned research manipulations has included stomach flushing, blood sampling, artificial brood reduction and other nest-related manipulations of eggs or chicks and attaching external devices to measure foraging behaviour. However, with the exception of one blood-sampling study (and double-banding), no individual fitness or population-level implications of research manipulations have been identified.

Another area of concern is the impact of flipper banding on Yellow-eyed penguin survival. Studies of other species indicate that in some cases flipper banding can be associated with higher energetic costs due to impairment of swimming ability, and thus lower survival, but this not true of all species. One study found there was a measurable negative impact on yellow-eyed penguins from double banding. A recent study found that individuals with previous exposure to the more intrusive research manipulations are less likely to habituate to short an consistent experimental disturbance. Both initial stress responses and habituation potential also depend on the sex and character of affected individuals, and the observed differences in behavioural and physiological stress responses are related to fitness parameters. Thus, human disturbance may drive contemporary evolutionary change in the composition of breeding populations with as yet unrealised consequences for conservation.

Another area of concern is the impact of flipper banding on Yellow-eyed penguin survival. Studies of other species indicate that in some cases flipper banding can be associated with higher energetic costs due to impairment of swimming ability, and thus lower survival, but this not true of all species. One study found there was a measurable negative impact on yellow-eyed penguins from double banding. A recent study found that individuals with previous exposure to the more intrusive research manipulations are less likely to habituate to short an consistent experimental disturbance. Both initial stress responses and habituation potential also depend on the sex and character of affected individuals, and the observed differences in behavioural and physiological stress responses are related to fitness parameters. Thus, human disturbance may drive contemporary evolutionary change in the composition of breeding populations with as yet unrealised consequences for conservation.

Marine threats

Fisheries:

The National Plan of Action to Reduce Incidental Catch of Seabirds in New Zealand Fisheries (MOF and DOC 2004) lists yellow-eyed penguins as by-catch in inshore set nest (set gillnets). However, historically there has been very low observer coverage (about 2%) of the inshore fishing fleet; hence there is little available information on the number of yellow-eyed penguins killed at sea each year due to fisheries activities. The absence of these data makes reliable impact assessment and the development of mitigation measures impossible. Between 1979 and 1997 there were a total of 72 confirmed deaths of yellow-eyed penguins in set-net entanglements, most at or near Otago Peninsula and set-net by-catch was thus considered to pose a significant threat. More recently fisheries observers have recorded the capture of four yellow-eyed penguins over three years (2006-09) of observer coverage of commericial set-net fisheries. There is also some evidence that indirect effects of commercial fisheries may have an impact on yellow-eyed penguin marine habitat degradation. The most recent inshore fishing fleet observer program reported five yellow-eyed penguins caught during a two month period (Jan/Feb 2009) covering only 13% of set-net effort during this time.

Fisheries:

The National Plan of Action to Reduce Incidental Catch of Seabirds in New Zealand Fisheries (MOF and DOC 2004) lists yellow-eyed penguins as by-catch in inshore set nest (set gillnets). However, historically there has been very low observer coverage (about 2%) of the inshore fishing fleet; hence there is little available information on the number of yellow-eyed penguins killed at sea each year due to fisheries activities. The absence of these data makes reliable impact assessment and the development of mitigation measures impossible. Between 1979 and 1997 there were a total of 72 confirmed deaths of yellow-eyed penguins in set-net entanglements, most at or near Otago Peninsula and set-net by-catch was thus considered to pose a significant threat. More recently fisheries observers have recorded the capture of four yellow-eyed penguins over three years (2006-09) of observer coverage of commericial set-net fisheries. There is also some evidence that indirect effects of commercial fisheries may have an impact on yellow-eyed penguin marine habitat degradation. The most recent inshore fishing fleet observer program reported five yellow-eyed penguins caught during a two month period (Jan/Feb 2009) covering only 13% of set-net effort during this time.

|

Oceanographic conditions and food supply:

There can be a marked inter-annual variation in food supply for yellow-eyed penguins with intermittent poor food years being marked by reduced numbers of breeding attempts, slow chick growth, higher pre-fledging chick mortality, low chick fledging weights and lower survival of juveniles and adults. Causes of poor seasons have not been conclusively identified but could be related to climate, including both periodic events such as the El Nino Southern Oscillations (ENSO event) and the inter-decadal Southern Oscillation, and long-term climate change. |

Pollution:

The wide geographical distribution of yellow-eyed penguins, the low intensity of shipping activities over much of the species range, and the low number of recorded spill incidents and proposals for their containment under the NZ Marine Oil Spill Response Strategy (Maritime New Zealand 2006), means oil and chemical spills are not considered a significant threat to yellow-eyed penguin populations at this time. However, there are proposals to permit oil exploitation in the western Foveaux Strait and to develop Dunedin as the major oil harbour of the South Island in the near future, with enlargement of shipping channels being planned. If these developments were to proceed, the entire mainland penguin population would be exposed to a higher risk of oil pollution and spills. |

Recommended priority research actions for conservation

IN 2009 New Zealand's Department of Conservation (DoC) circulated a draft document titled "Research and Management Priorities for Yellow-eyed penguins" which called for, among other things the "development of a research agenda with an emphasis on identifying the important gaps in our knowledge of yellow-eyed penguins". An immediate outcome of this document saw an ad hoc yellow-eyed penguin Research advisory Group (YEP RAG) formed in order "to provide a research framework and to make associated recommendations for methods and process to address current research priorities with regard to yellow-eyed penguins". DoC has affirmed that the annual recording of the reproductive performance of marked individuals at selected sites must be sustained so as to contribute to an electronic relational database maintained by DoC and currently containing more than 20 years of data. A key approach for future research will entail the interrogation of this unique research resource.

Research priorities include the following:

1. Identify determinants of inter-annual and regional variation in yellow-eyed penguin productivity.

2. Systematically collate data on breeding site characteristics, annual reproductive performance, management intervention, and climatic and oceanographic indicators at local and regional scales across selected sites through the penguin's range.

3. Unify and direct what have been enthusiastic but disjointed regional data gathering exercises.

4. Identify specific projects that may be suitable for ongoing monitoring or one-time studies.

Research priorities include the following:

1. Identify determinants of inter-annual and regional variation in yellow-eyed penguin productivity.

2. Systematically collate data on breeding site characteristics, annual reproductive performance, management intervention, and climatic and oceanographic indicators at local and regional scales across selected sites through the penguin's range.

3. Unify and direct what have been enthusiastic but disjointed regional data gathering exercises.

4. Identify specific projects that may be suitable for ongoing monitoring or one-time studies.

Current conservation efforts

Current conservation efforts fall into three categories.

Current conservation efforts fall into three categories.

Habitat protection and restoration

Habitat protection and restoration (including predator control) is managed on a site-by-site basis by the Department of Conservation, the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust, community groups, and private landowners. The Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust currently administers 7 breeding areas, 3 on the Otago Peninsula totalling over 250ha, 1 in North Otago, and 3 in the Catlins. On Trust sites, active habitat restoration includes trapping exotic mammalian pests (primarily mustelids and cats) and planting native vegetation to convert former grazed pasture to coastal shrubland. Selected DoC sites have been revegetated, are subject to seasonal predator trapping of mustelids, and may limit public access at sensitive periods during the yellow-eyed penguin breeding season, several privately owned sites on the Otago Peninsula are a focus of nature based tourism operations and undertake regular predators trapping and habitat enhancement, including controlled grazing by livestock, revegetation, or provision of nest boxes. Nes boxes have been used successfully as temporary measure to provide concealment until revegetation is sufficiently advanced.

Habitat protection and restoration (including predator control) is managed on a site-by-site basis by the Department of Conservation, the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust, community groups, and private landowners. The Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust currently administers 7 breeding areas, 3 on the Otago Peninsula totalling over 250ha, 1 in North Otago, and 3 in the Catlins. On Trust sites, active habitat restoration includes trapping exotic mammalian pests (primarily mustelids and cats) and planting native vegetation to convert former grazed pasture to coastal shrubland. Selected DoC sites have been revegetated, are subject to seasonal predator trapping of mustelids, and may limit public access at sensitive periods during the yellow-eyed penguin breeding season, several privately owned sites on the Otago Peninsula are a focus of nature based tourism operations and undertake regular predators trapping and habitat enhancement, including controlled grazing by livestock, revegetation, or provision of nest boxes. Nes boxes have been used successfully as temporary measure to provide concealment until revegetation is sufficiently advanced.

Tourism management

The yellow-eyed penguin is a major nature-based tourism attraction on mainland South Island. Commercial wildlife tourism takes place on both private land and under DoC concession on DoC-administered reserves. Unregulated visitor access is facilitated at some 20 key mainland sites with the intention of taking visitors pressure off more sensitive areas. At unregulated sites, signage, viewing hies, and, in some cases, a volunteer warden scheme is used to mitigate impacts. There is some well-regulated seasonal tourist presence at yellow-eyed penguin landing and nesting areas on Enderby Island, in the Auckland Island group. However, much of this must rely on capped tourist numbers, goodwill, and adherence to DoC's Subantarctic Minimum Impact Code and landing permit schedules.

The yellow-eyed penguin is a major nature-based tourism attraction on mainland South Island. Commercial wildlife tourism takes place on both private land and under DoC concession on DoC-administered reserves. Unregulated visitor access is facilitated at some 20 key mainland sites with the intention of taking visitors pressure off more sensitive areas. At unregulated sites, signage, viewing hies, and, in some cases, a volunteer warden scheme is used to mitigate impacts. There is some well-regulated seasonal tourist presence at yellow-eyed penguin landing and nesting areas on Enderby Island, in the Auckland Island group. However, much of this must rely on capped tourist numbers, goodwill, and adherence to DoC's Subantarctic Minimum Impact Code and landing permit schedules.

Rehabilitation

Under DoC authority, there are three approved rehabilitation centres for yellow-eyed penguins. These privatley funded centres serve as collection point for sick, injured, or orphaned penguins, and for penguins that have not moulted in good condition. They also act as focal points for management responses to periodic disease outbreaks during the breeding season. A recent evaluation of rehabilitation outcomes found that although rehabilitation of resident breeders did not generate a significant increase in mean annual survival, it can increase the local number of nesting attempts at sites where anthropogenic threats to the species are adequately managed.

Under DoC authority, there are three approved rehabilitation centres for yellow-eyed penguins. These privatley funded centres serve as collection point for sick, injured, or orphaned penguins, and for penguins that have not moulted in good condition. They also act as focal points for management responses to periodic disease outbreaks during the breeding season. A recent evaluation of rehabilitation outcomes found that although rehabilitation of resident breeders did not generate a significant increase in mean annual survival, it can increase the local number of nesting attempts at sites where anthropogenic threats to the species are adequately managed.

Recommended priority conservation actions for increasing resilience and minimising threats and impacts

The long-term goal of the 2000-2025 Recovery Plan for the yellow-eyed penguin is to increase the population. As of 2010, effective seasonal predator control was in place for 22 of a total of 38 principal mainland sites, thus meeting the goal of protection of chicks from predators as 50% of all South Island nests. Fisheries activities (via by-catch and alteration of foraging habitat and prey availability) have been postulated to have an impact on penguin breeding along the northern coasts of Stewart Island and may negatively affect the mainland populations. Recommendations are as follows:

1. Sustain and expand protection of chicks from predators at mainland sites.

2. Manage other anthropogenic threats, particularly human disturbance, at mainland sites.

3. Evaluate numbers and trends for sub-Antarctic populations and identify possible limiting factors.

4. Quantify the impact of commercial fisheries via by-catch, marine habitat degradation, and overfishing of spawning stock throughout the yellow-eyed penguin range.

The long-term goal of the 2000-2025 Recovery Plan for the yellow-eyed penguin is to increase the population. As of 2010, effective seasonal predator control was in place for 22 of a total of 38 principal mainland sites, thus meeting the goal of protection of chicks from predators as 50% of all South Island nests. Fisheries activities (via by-catch and alteration of foraging habitat and prey availability) have been postulated to have an impact on penguin breeding along the northern coasts of Stewart Island and may negatively affect the mainland populations. Recommendations are as follows:

1. Sustain and expand protection of chicks from predators at mainland sites.

2. Manage other anthropogenic threats, particularly human disturbance, at mainland sites.

3. Evaluate numbers and trends for sub-Antarctic populations and identify possible limiting factors.

4. Quantify the impact of commercial fisheries via by-catch, marine habitat degradation, and overfishing of spawning stock throughout the yellow-eyed penguin range.